Media Contact

Haemophilia is a rare, inherited bleeding disorder where the blood doesn’t clot properly due to a lack of blood-clotting proteins. Our experts help treat these disorders and help patients to live a safe and healthy life.

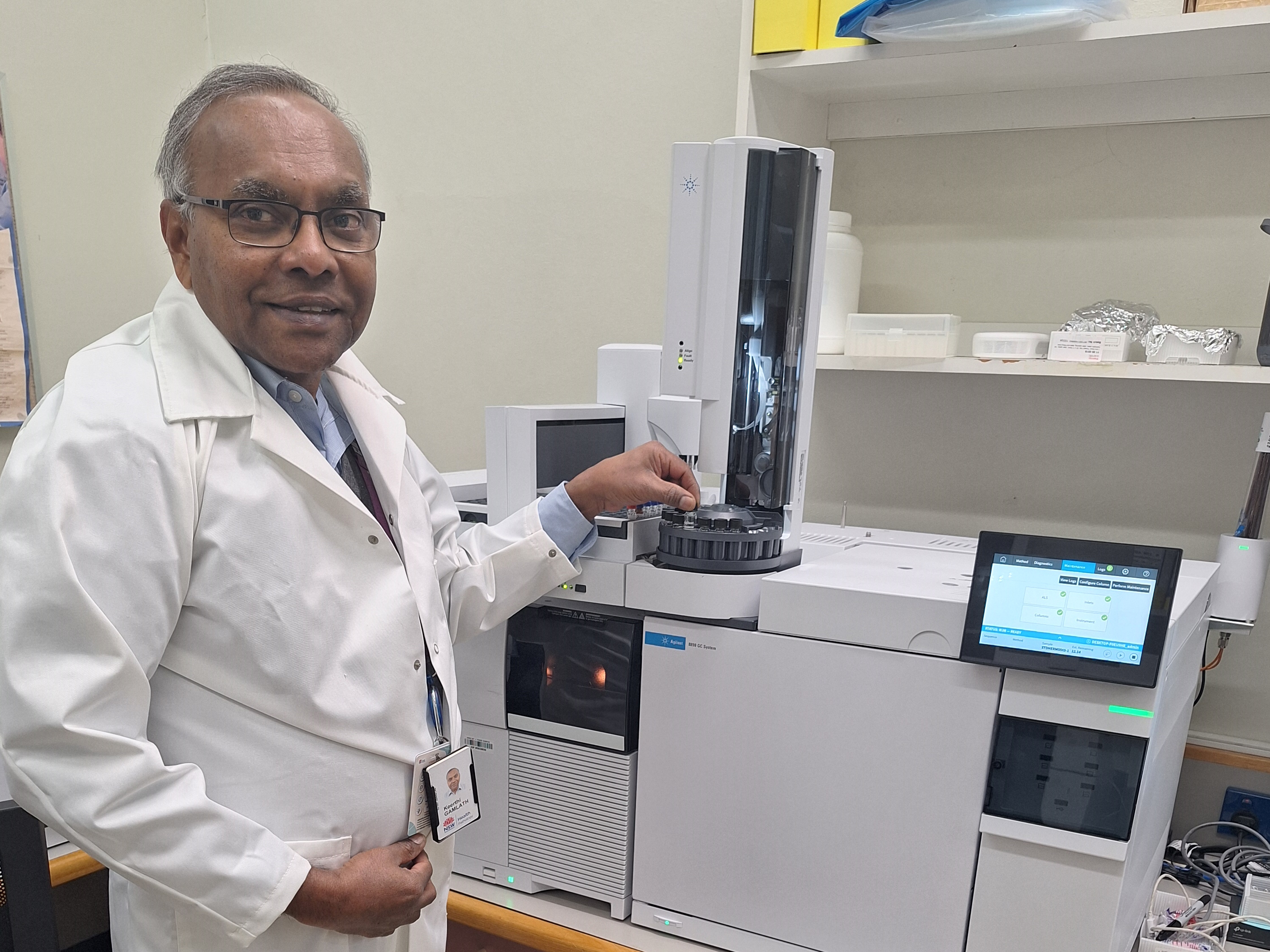

Kent Chapman is NSW Health Pathology’s senior hospital scientist in charge of haemostasis or coagulation at Newcastle’s John Hunter Hospital.

“For those not familiar with it, that’s all the bleeding and clotting stuff,” he explains.

He says blood disorders often capture people’s attention, particularly haemophilia, because it is so rare and can be very dangerous.

“It is particularly rare, affecting about 1 in about 6 to 10,000 males and less than 1 in 300,000 females,” he says.

“Newcastle is the only haemophilia centre outside of Sydney, so we cover a large area of NSW, looking after patients from here to Tweed Heads and as far west as you can go.

“We help to manage about 70 children and about 400 adults with bleeding disorders.

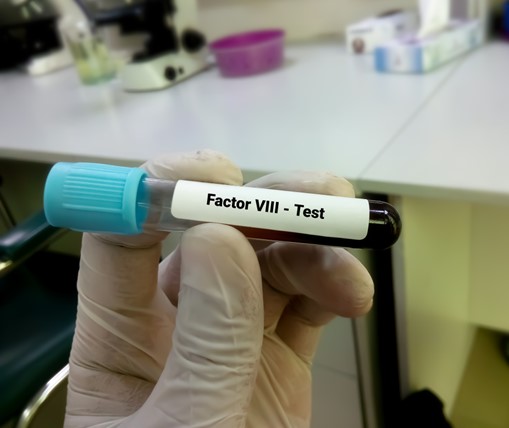

“They range in severity from those with very mild cases, who we only treat on demand, to those who require product or factor VIII replacement every day, so they don’t have catastrophic bleeds.”

There are two major types of haemophilia:

• Haemophilia A is the most common form and is caused by having reduced levels of clotting factor VIII (eight).

• Haemophilia B, also known as Christmas Disease, is caused by having reduced levels of clotting factor IX (nine). The disease was named after Stephen Christmas, who was the first person diagnosed with the condition in 1952.

The ‘Royal Disease’

Haemophilia has also been called a ‘royal disease’. This is because the haemophilia gene was passed from Queen Victoria (haemophilia B carrier), who became Queen of England in 1837, to the ruling families of Russia, Spain and Germany.

Mr Chapman says the type most people have heard of is haemophilia A.

“The good news is the treatment for that is quite amazing, it’s come a long way in the last few years.”

He says a new product that has only become available in Australia in the last couple of years means patients don’t have to inject factor VIII every day, but only once every week or two.

The injection is also subcutaneous, rather than intravenous, which has made an enormous difference to the lives of many patients.

“It means if they’re on this product, they’ll have the same sort of life expectancy that you or I would have.

“Obviously they still have to be mindful of playing contact sports and all those types of things, but they have a much better quality of life, which is great.”

But Mr Chapman admits the improvement in haemophilia A treatment has made things slightly more complicated for his laboratory.

“Trying to monitor these different products in the lab can become more challenging.

“We’ve had to use different tests to be able to monitor these new therapies, and the new therapies get in the way of the testing for the way we used to do it.

“It’s made our work more complicated, but it’s exciting because it’s much better for people living with haemophilia.”

Other blood disorders

Mr Chapman has a particular interest in the clotting side of blood disorders and has spent time working on a group of disorders called thrombotic microangiopathies.

“We established testing for a particularly rare and fatal disease here over 10 years ago called thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura,” he explains.

“It’s a particularly horrible disease where you basically start having blood clots from head to toe, particularly in the small blood vessels.

“If not detected early, you have a very high chance of dying within a couple of days of diagnosis.

“But with the appropriate diagnosis and treatment 95% of patients are okay.

“The treatment is quite intensive and involves plasma exchange, which is basically sucking all the patient’s plasma out and replacing it with more plasma, and that can take weeks until the patient goes into remission.”

Mr Chapman says he has been particularly fortunate to be working in the field of haemostasis, with talented colleagues and mentors, such as NSW Health Pathology’s Dr Emmanuel Favaloro (Westmead) and Geoffrey Kershaw (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown).

“There are not too many people who get to do this type of work, so I’m very grateful to have ended up here,” he says.

“It was a bit of a fluke that I ended up in pathology to be honest. My mother knew someone who worked in a path lab, she told me to get a haircut and helped get me the job.

“Twenty-something years later, here I am!”