Media Contact

May 31 is Necrotizing Fasciitis (NF) Awareness Day when we share information on the treatment and prevention of the most common flesh-eating disease in the world today.

NF is a bacterial infection that can cause the death of skin, muscle and tissue, and organ failure if left uncontrolled. Treatment often involves surgery, antibiotics, and supportive care to prevent further infection and damage. Life-saving limb amputation is often required.

It’s been around a long time

Hippocrates, the father of medicine, first described NF more than 2000 years ago, reporting people developing skin infections that caused bones, flesh and sinew to ‘fall off from the body’ resulting in many deaths.

Surgeons in the American Civil War called it ‘hospital gangrene’.

Today, NF is still affecting people including 2001 Nobel Prize-winning Physicist Professor Eric Cornell, who lost an arm and shoulder to the disease. The United States Centre for Disease Control says up to 1 in 5 people who develop NF will die.

How do you get NF?

It’s mostly caused by bacteria entering the body through a break in the skin from cuts and scrapes, burns, bites, surgical wounds and punctures including from IV drug use.

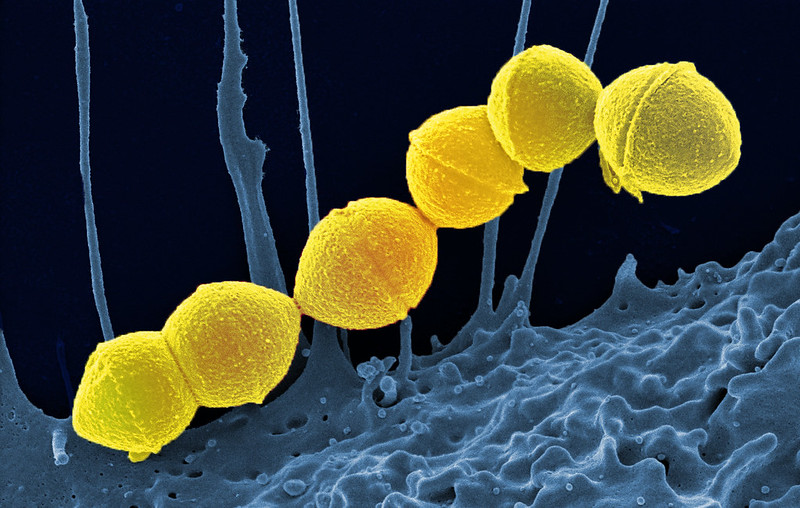

The most common bacteria involved in NF is A Streptococcus, also known as Group A strep or GAS. It lives on our skin and in our throats without causing harm, but in open wounds it can fester, releasing toxins that cause septic shock, making blood pressure drop, which can cause body tissue to die.

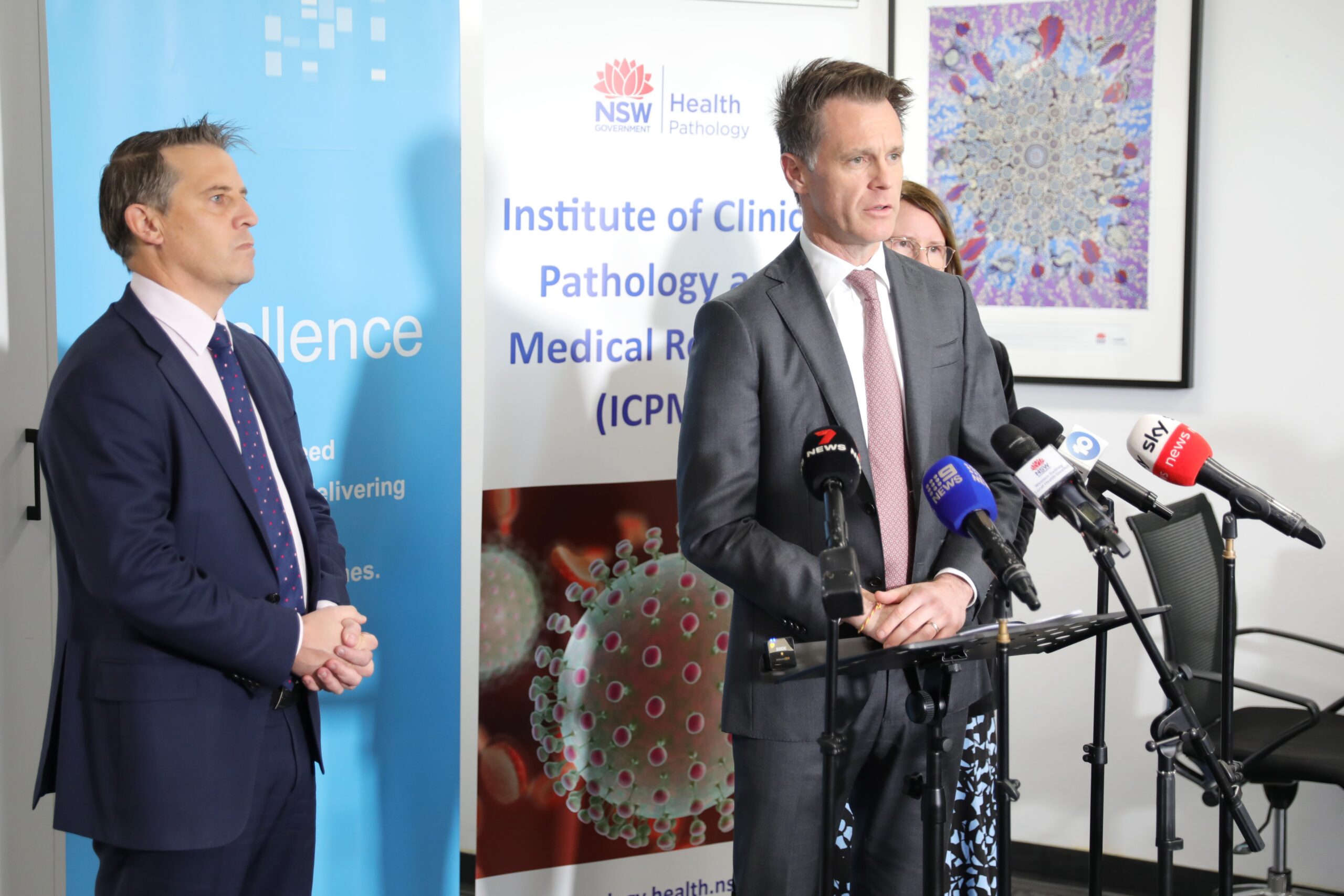

While NF infections are incredibly rare in healthy people, cases are on the rise in the United Kingdom, the United States and Europe. NSW Health Pathology’s Institute for Clinical Pathology and Medical Research (ICPMR) advises there is evidence of increasing GAS cases in NSW and Victoria as well.

How do you avoid NF?

Those who develop it tend to have other health problems that lower their immunity such as cancer, diabetes and kidney disease.

There are no vaccines to prevent GAS infection but you can do simple things to protect yourself such as:

- Wash your hands and use hand sanitiser to kill bacteria and prevent transmission

- Clean cuts and wounds with water and soap and bandage open wounds until healed

- See a doctor for more serious wounds and punctures

- If you have open wounds, avoid rivers, lakes and swimming pools where bacteria live

- Treat fungal infections, because fungi may also cause NF

How we’re helping

NF is typically diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluation, CT scans and MRI, and laboratory testing.

Our laboratories perform rapid culture and sensitivity testing to identify which bacteria is at work and advise treating doctors which antibiotics to use to kill them. We test blood and wound cultures as well as tissue biopsies. Other tests performed to support NF diagnosis are complete blood counts, C‑reactive protein to gauge inflammation and coagulation profiles for very ill patients.

That’s not all we do

Our work also extends to public health protection and research.

We use whole genome sequencing to study and understand NF-causing bacteria. It can show how they work, if they are related and how they can be treated. It’s like looking at a unique blueprint of the bacteria that helps us learn more about them.

Given increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance there is an urgent need for the development of new antimicrobials and continual review of antibiotic treatment guidelines to ensure they remain effective. Our NSWHP-ICPMR Microbiology Department tests novel antibiotics against a range of bacteria including drug combinations and shares data nationally.

NF is not the only flesh-eating disease we manage

The world-class expertise of our clinical and scientific staff means we’re often the first port of call for investigation of other highly uncommon flesh-eating diseases.

These include those caused by M. ulcerans (buruli ulcer, sometimes called ‘Bairnsdale ulcer’, because it was first detected in that region of Victoria almost 100 years ago) and M. leprae (leprosy). Others are other traumatic mucormycosis and other invasive fungal infections, and cutaneous nocardiosis.

Thankfully, our experts have knowledge and experience to recognise, diagnose and treat these infections.

MEET A CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGIST

Dr Kerri Basile, what is your role?

I work as a clinical microbiologist and infectious diseases physician at NSWHP-ICPMR.

What are your qualifications?

I undertook a medical degree (MBBS) and then completed specialist training in Microbiology (FRCPA) and Infectious Diseases (FRACP) and am currently undertaking a PhD.

Why do you like it?

I enjoy my work as it is varied, with constant opportunities to learn and be challenged. Working in the laboratory is extremely rewarding as advances in diagnostics such as whole genome sequencing have the potential to improve the health of individual patients as well as the wider community. Whole genome sequencing is being increasingly utilised to monitor pathogens of public health significance (such as SARS-CoV‑2 during the COVID-19 pandemic).

How do you keep safe while handling these microbes?

Safety is a top priority in the laboratory. We deal with thousands of samples each day, and many unknowns, so until we know the identity of the bug we perform all our culture work up in a Biological Safety Cabinet.

For highly infectious pathogens we may work in a lab with custom airflow and pressure properties as a further precaution.

We wear personal protective equipment including gowns, gloves, goggles and/or face masks. Hand washing is essential. We’re immunised against many vaccine-preventable infections.

Has your experience with these bugs changed your habits?

Yes, I’m very careful with wounds. But this doesn’t stop me enjoying travel and the outdoors.

Make sure you get the tetanus booster before you set out and be aware of injuries

Resources, references and further reading

- https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-public/necrotizing-fasciitis.html

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099%2814%2970922–3/fulltext

- https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/buruli-ulcer

- Eric Allen https://www.nature.com/articles/434945a

- https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/condition/necrotizing-fasciitis

- https://time.com/4984752/flesh-eating-bacteria-necrotizing-fasciitis/