NSW’s most remote hospitals will soon perform a key, potentially life-saving blood test at the patient’s bedside and receive results within minutes, providing clinicians with fast, accurate results to inform patient care.

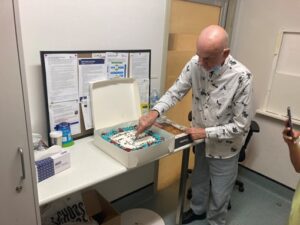

NSW Health Pathology is partnering with five regional Local Health Districts to introduce a new Point of Care Testing device, the PixCell Hemoscreen, in 30 hospitals across the state without on-site pathology labs.

The device will allow doctors and nurses to perform one of the most routinely ordered pathology tests, a Full Blood Count, to detect potentially life-threatening conditions such as sepsis, anaemia, bleeding and blood clotting problems (ie low platelet counts).

The devices will be rolled-out to services in coming months, along with training to support hospital staff to safely and effectively operate the machine and to follow-up on abnormal results.

Gayle Warnock, Acting Operations Manager, NSW Health Pathology’s Point of Care Testing Service, said the device will provide blood test results within six minutes, rather than waiting for blood samples to be transported and tested at a lab sometimes hours away.

“This is a game changer for hospitals that do not have on-site pathology labs and the patients they care for,” Galye said.

“Traditionally, these rural and remote hospitals would take a blood sample and have it couriered to the closest NSW Health Pathology lab for analysis, sometimes hundreds of kilometres away.

“Now clinicians can perform this test instantly at the patient’s bedside so they can make timely, informed decisions about patient care. This could include whether the person can continue receiving care in their local hospital or if they need to be transferred to a more specialised facility for treatment,” Gayle said.

“Repeating the Full Blood Count test during the patient’s treatment also helps hospital staff understand whether the person’s condition is improving.”

Our Point of Care Testing service completed an extensive trial period, known as verification, of the PixCell device in consultation with our experienced haematologists prior to starting the roll-out.

A clear process was put into place to ensure all samples that are abnormal, or from patients with known blood disorders, are reviewed by a haematologist.

“These samples will be repeated in laboratories via our usual testing processes to ensure patients, and the hospital staff caring for them, receive high-quality, accurate pathology results to inform their care,” Gayle said.

“NSW Health Pathology will also closely work with hospital staff to monitor the overall service and performance of the devices, and ensure they’re managed to the same high standards as traditional lab instruments.”