Media Contact

Maggot therapy has been around for centuries and is still used in our hospitals today to treat particularly troublesome wounds. But where do the maggots come from?

Deep in the basement of Westmead Hospital is a door with a warning sign which reads: Insectary- ensure air curtain is ON while room is in use.

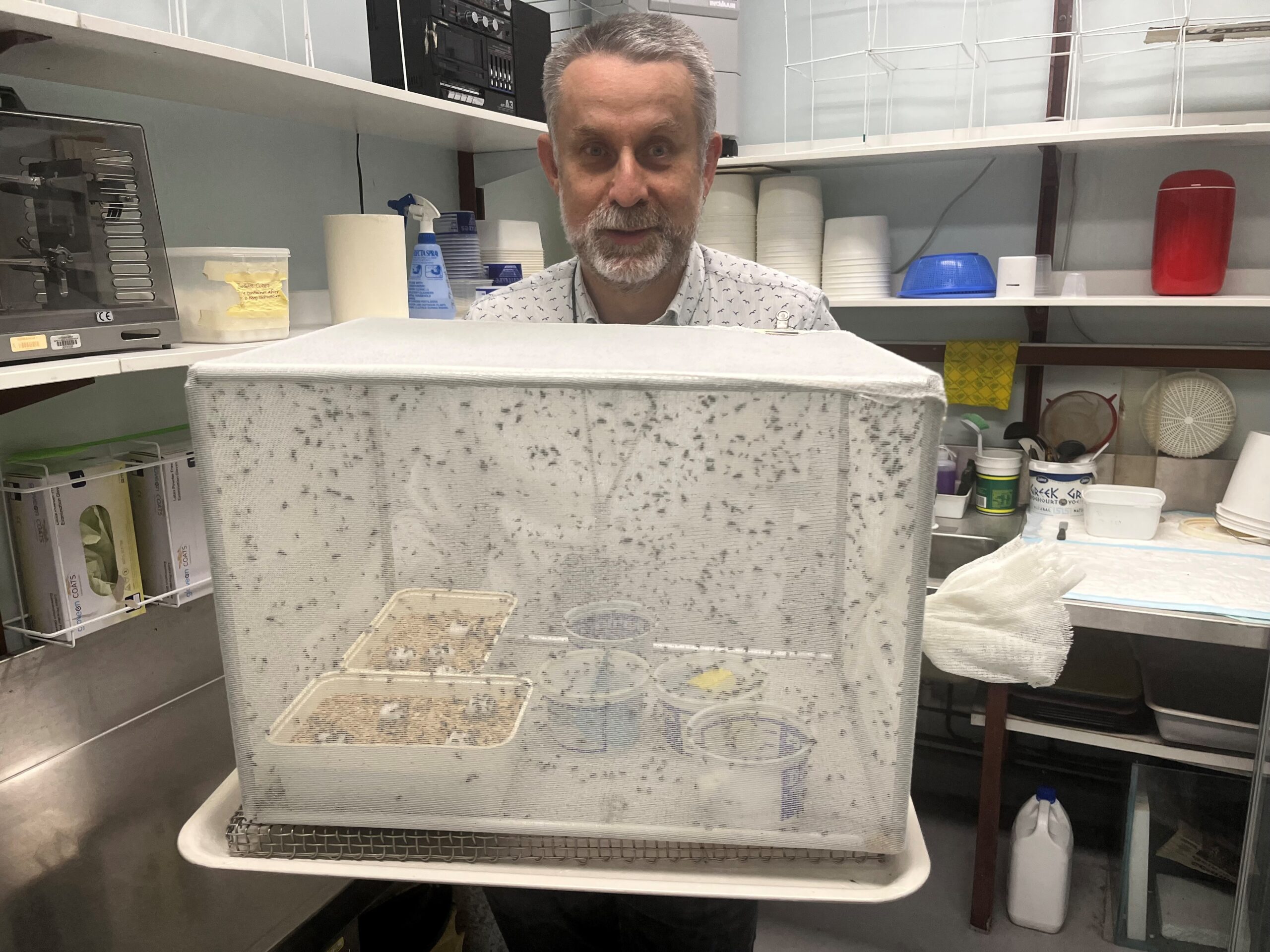

Inside are a series of mesh cages filled with flies and they are carefully looked after by a small team of dedicated scientists.

It’s where NSW Health Pathology’s Medical Entomology team harvests the maggots that are used by hospitals across Australia, and even sent to health services overseas, to treat patients whose wounds are not responding to more conventional medical treatments.

They are the sole suppliers of maggots for medical purposes in Australia.

How does maggot therapy work?

Maggot debridement therapy (MDT) involves placing sterile fly larvae (live maggots) on open wounds to assist in the removal of dead and infected tissue.

The maggots are the immature stage of the fly species Lucilia sericata, a common blowfly. It is the main species of fly utilised worldwide for MDT, as the fly’s young have the unique feeding behaviour of devouring devitalised tissue, whilst leaving the surrounding healthy tissue intact. (1)

MDT was once a routine procedure in hospitals throughout Europe, the US and Canada during the 1930s and early 1940s. The medical journals from this era list osteomyelitis, abscesses, carbuncles, burns, cellulitis, gangrene, and leg ulcers as having been successfully treated. But with the advent of antibiotics and the development of new surgical techniques MDT slipped into obscurity.

However, interest was revived when medical trials in the 1980s concluded the therapy still had many benefits to offer patients in the treatment of chronic wounds. Not only do the maggots remove necrotic tissue in a precise manner, but they also assist in controlling infection and promote the regeneration of healthy tissue and healing.

How do we harvest maggots?

The insectary at the Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research at Westmead Hospital’s was established by Merilyn Geary around the year 2000 to provide a disinfected source of maggots for medical purposes.

NSW Health Pathology’s Director of Medical Entomology Stephen Doggett (pictured top) says ensuring the maggots are clean is a vital first step in the process.

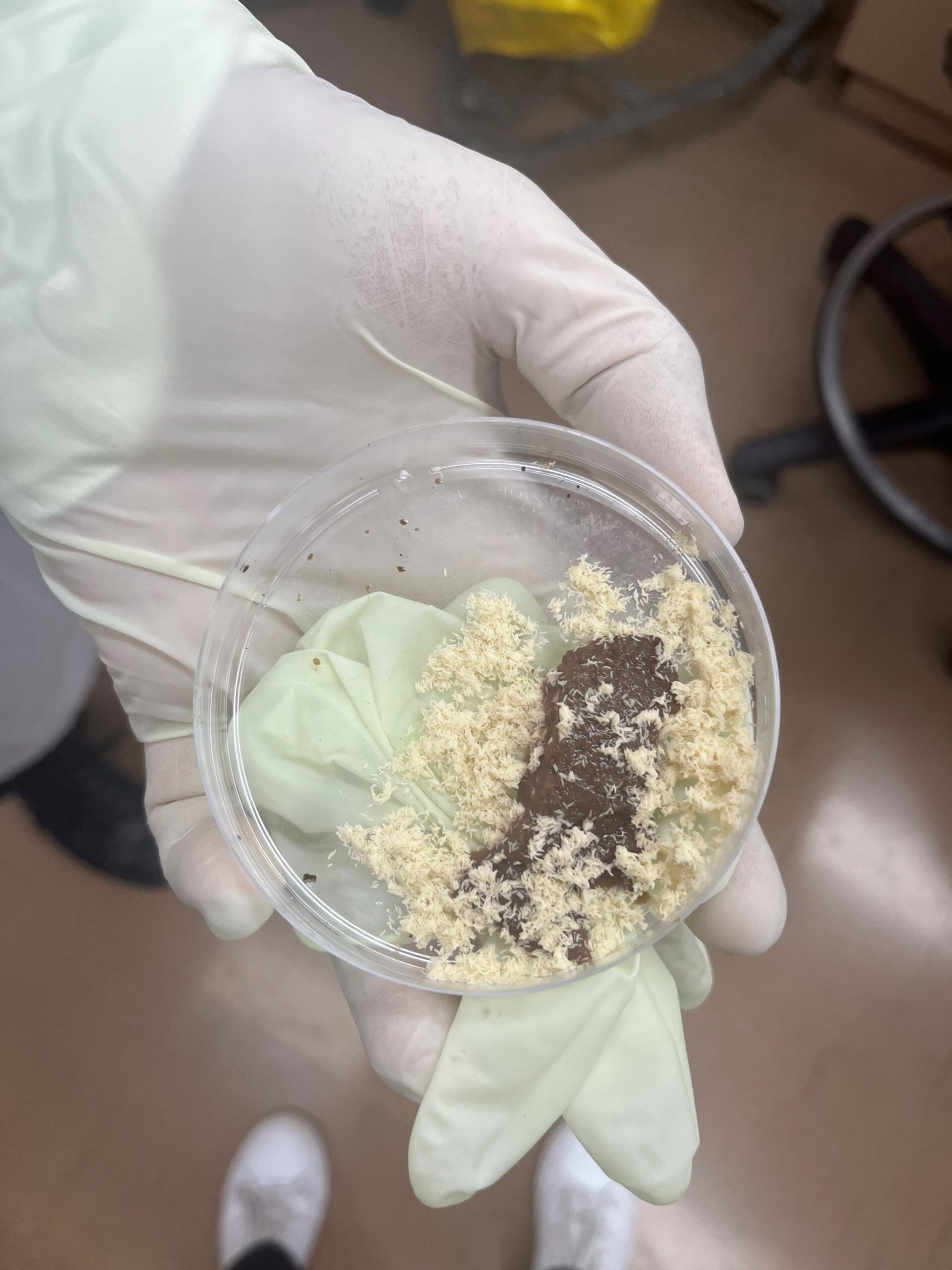

“Once the flies lay their eggs, we wash the eggs with an antiseptic solution to remove any bacteria,” he said.

“The eggs are then collected and put into a sterile media to grow – we use egg yolk and that’s what they grow in.

“After they hatch there are three larval stages, and we breed them until they hit the second stage. They are then collected and packed into vials, after checks that they are free of bacteria, to send off to where they are needed,” Stephen explained.

Each vial contains about 100 maggots, and they are placed directly onto the patient’s wound.

The wound is then bandaged with special material to keep the maggots in place, while also allowing airflow to the wound. The maggots are left on the wound for two days and after they do their work, they are removed by nursing staff and disposed of.

Is it making a comeback?

Stephen says depending on the size, depth and complexity of the wound, a patient may need more than one application of maggots.

“In most cases simple wounds would only need one application, but we did have a case a few years back when a patient required 45 applications before his wound was under control.

“The treatment was ultimately successful and avoided what would otherwise have almost certainly been the amputation of his foot.”

He thinks it’s a treatment that has found its time again.

“It is taking time to find acceptance in the medical community, but once a patient receives the treatment, they say they would have it again.

“We have a situation where antibiotic resistance is growing. Maggot therapy is cheap, and it works.”

1. Merilyn J Geary, The Broad Street Pump, April 2010