Researchers at NSW Health Pathology and the University of Sydney are working together to design a new integrated legionellosis surveillance system, using genomic testing to improve detection of legionella outbreaks.

Legionnaires’ disease is an infection of the lungs that is spread to humans by breathing in droplets of water contaminated with legionella bacteria. The most common sources of this bacteria are air conditioning cooling towers.

There have been several large outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in Sydney in the past few years, and public health authorities need better tools to help them control outbreaks more quickly.

A new research project is aiming to bring together the latest in genomics technology and a range of public health organisations to improve how we detect and respond to outbreaks.

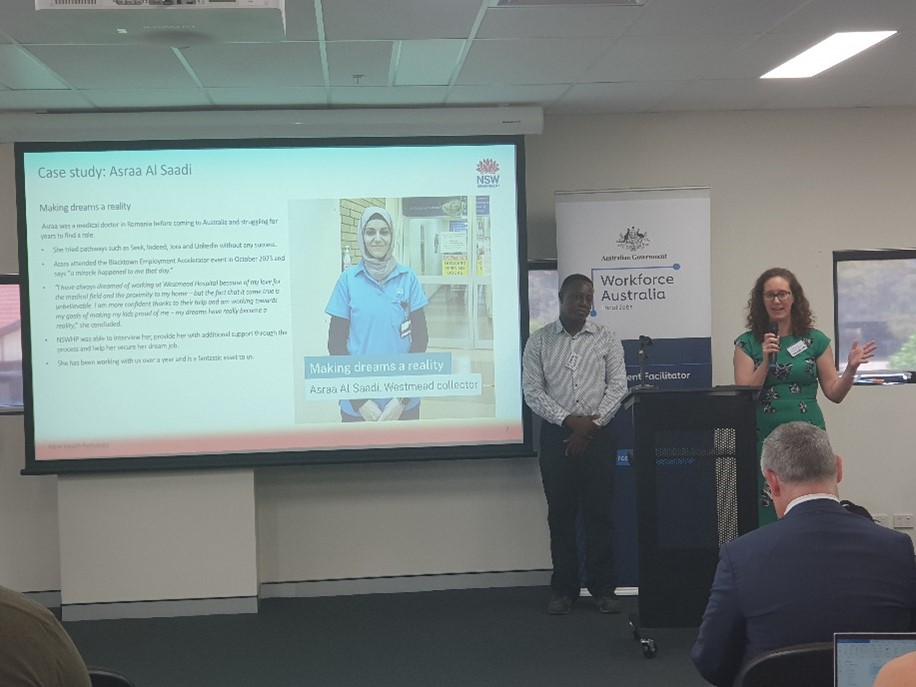

NSW Health Pathology (NSWHP) is the host organisation for the project being led by Chief Investigators, Professor Vitali Sintchenko (NSWHP and University of Sydney) and Dr Eby Sim (University of Sydney). (pictured above)

The research team is also partnering with Health Protection NSW, and Public Health Units, in Western Sydney and South East Sydney Local Health Districts.

They’ve been awarded a $500,000 Translational Research Grant through the NSW Office of Health and Medical Research to assess the effectiveness of whole-genome sequencing for integrated surveillance for legionellosis.

“Public Health authorities aim to identify clusters of cases as soon as possible in order to remove the source of infection and prevent further spread in the community,” Vitali explains.

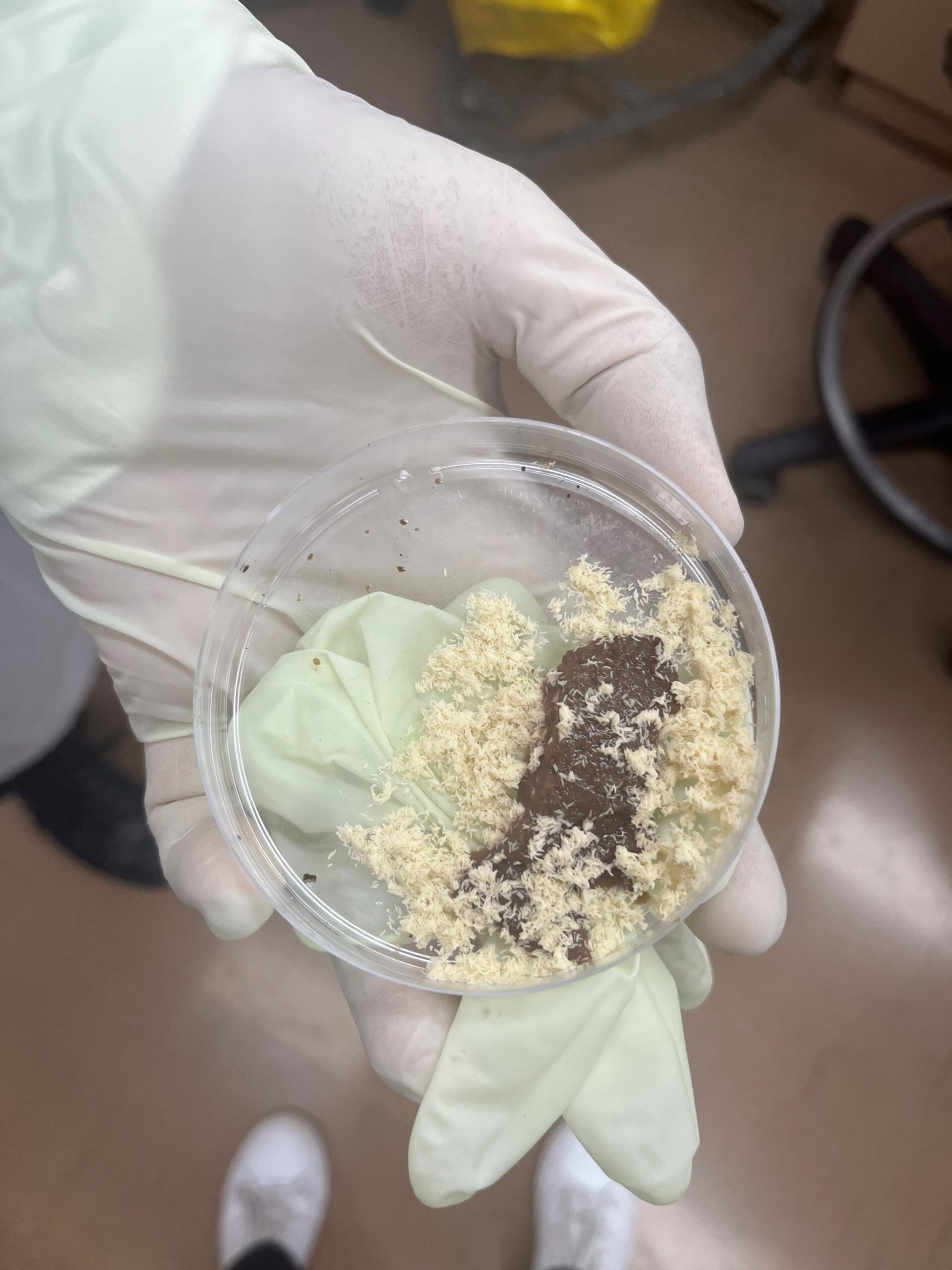

“Growing Legionella in the lab is a complex process, it takes a long time, and cultures are not often available because more cases of legionella infection are diagnosed by PCR testing.

“So, this project is going to use clever genomics that can collect genomic information without culture directly from respiratory samples. That will increase the number of relevant cases that can be investigated without relying on culture.

“The other part of the project is to bring together multiple stakeholders – public health units, specialists in environmental health, clinical and environmental microbiology.

“Our team is focused on a whole-of-system approach so that different types of data can be mapped together, and genomics can hopefully save time by identifying commonalities, or links between cases, that otherwise would not have been recognised as part of a cluster.”

Dr Eby Sim says the genomic sequencing technology being used by the research team at Westmead will significantly streamline the process of searching for matches between samples.

“Legionella is hard to grow in a laboratory, and the culture takes many days,” he said.

“Here, we are attempting to bypass the growth of Legionella pneumophila in the laboratory and directly ‘fish out’ its genomic signature from a specimen, which is very helpful for linking cases and clusters together.”

“We also want to make sure that outbreaks don’t keep expanding so we can assist public health units in finding hot spots and responding to them faster,” said Eby.

Vitali says the research project will take two years to complete.

“The success of this competitive grant application is due to our partnership between Health Protection NSW, the University of Sydney and also support from ICPMR and NSW Health Pathology’s Public Health Pathology office.

“What we want to see, if everything goes as we planned, is that NSW Health Pathology’s genomics is integrated into the environmental and public health monitoring and response, reducing the time it takes to identify clusters of legionellosis.”