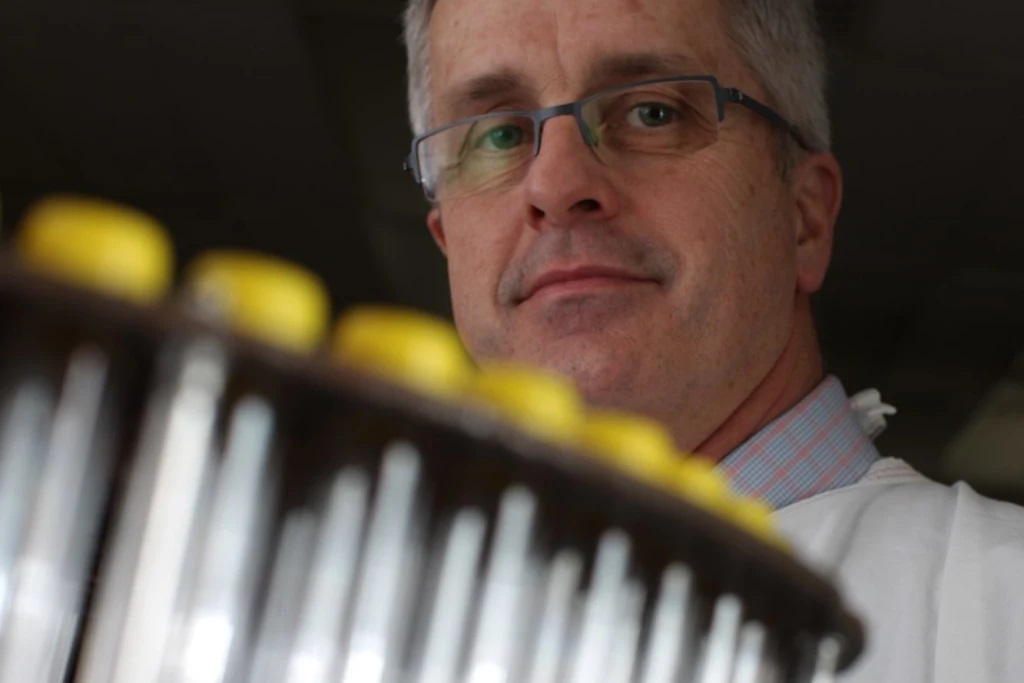

He became the public face of our pathology services during the COVID-19 pandemic, but now Professor Dominic Dwyer PSM is retiring after more than four decades dedicated to researching, diagnosing, and treating infectious diseases.

Professor Dominic Dwyer PSM is a world-renowned medical virologist and infectious diseases physician at NSW Health Pathology’s Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research (ICPMR) at Westmead Hospital.

His long and distinguished career spans nearly 42 years and has taken him all over the globe to investigate viral outbreaks that threaten the safety of communities.

When he’s not consulting with international experts or sharing his insight and experience at health conferences, he has been a trusted spokesperson on public health and emerging infections.

We’ve lost count of how many media interviews he has enthusiastically given during the COVID-19 pandemic and he is a globally renowned researcher with over 500 published papers.

Dominic undertook postgraduate research in HIV/AIDS at the Institute Pasteur in Paris, France, before going on to the lead the World Health Organization (WHO) National Influenza Centre in Westmead.

He has extensive experience in pandemic responses, even prior to COVID-19. His work in molecular testing for HIV spans three decades and he assisted the WHO to manage the SARS outbreak in China nearly 20 years ago.

“Dominic has been an exemplary public servant and a role model for collaborative leadership and innovative ideas,” NSW Health Pathology Chief Executive Vanessa Janissen said.

“He’s a trusted voice in the laboratory, in the clinic and the media, but perhaps his biggest test came with the devastating global COVID-19 pandemic.

“Working around the clock, he marshalled our expert ICPMR-Westmead team, developing scientific breakthroughs to advance the health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

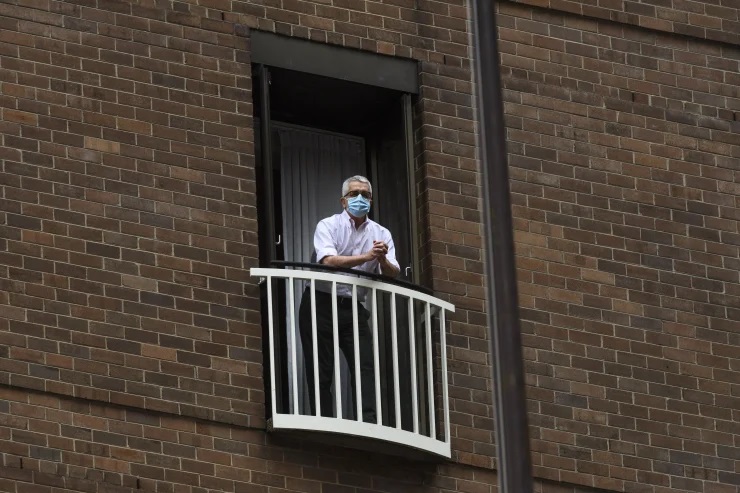

In 2020 Dominic was selected by the WHO to be part of an international team of physicians, scientists and researchers to explore the origins of the coronavirus in Wuhan, China.

Dominic’s contribution to the pandemic response earned him an Honourable Mention in the 2021 NSW Public Servant of the Year award.

He was awarded the Public Service Medal in the 2022 Australia Day Honours List for outstanding public service as an infectious disease expert and public health advisor in NSW, and the French Government’s ‘Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite’ in 2021 for COVID-19 services.

Congratulations on a stellar career Dominic, and we wish you a long and enjoyable retirement!