In this story

Media Contact

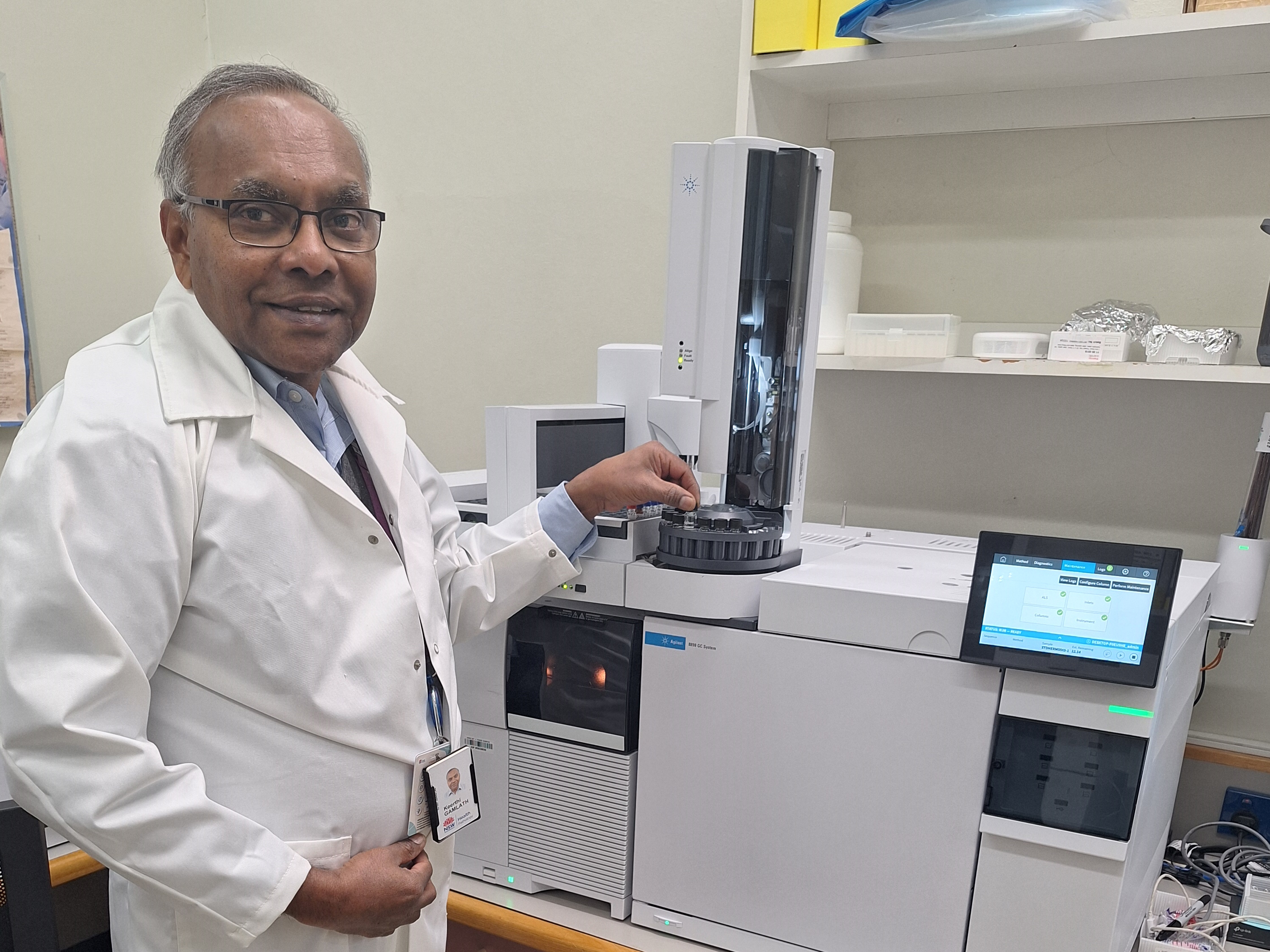

Dr Emmanuel Favaloro’s passion and expertise lie in bleeding disorder diagnosis and better patient care.

People with these disorders bleed excessively. With up to 1% of the world’s population potentially suffering from von Willebrand disease (VWD) according to epidemiological studies, it is considered by far to be the most common bleeding disorder. However, since most people experience very mild symptoms, it is estimated that globally as many as 9 out of 10 people with VWD have not been diagnosed.

Dr Favaloro is a Laboratory Scientist at NSW Health Pathology, Westmead ICPMR who specialises in laboratory testing for clotting disorders, including von Willebrand disease (VWD). According to a recent study, Emmanuel is the most prolific author on von Willebrand Disease.

“When we talk about bleeding disorders, most people think about Haemophilia,” he said.

Haemophilia A and B are characterised by a reduction in the function of the proteins Factor VIII or Factor IX, which are important for blood clotting. VWD is defined as the lack of or reduced function of a protein called von Willebrand Factor (VWF) in our blood.

VWF has several purposes. Following injury, VWF in your blood plasma attaches to platelets and helps to clump them together to immobilise them. VWF also binds to the injured tissue itself to help form a ‘platelet plug’ or ‘platelet clot’ to block the hole and stop bleeding.

People with VWD either don’t have any VWF, have less VWF or the VWF doesn’t work properly, so they continue to bleed.

Symptoms can include:

- Excessive bleeding from cuts or surgery

- bleeding from the gums during dental work

- frequent nosebleeds that do not stop within 10 minutes

- heavy or long menstrual bleeding

- heavy bleeding during childbirth

- blood in urine or stool

- bruising easily or lumpy bruises.

Surgery is one of the key concerns for people with VWD because of the increased risk of bleeding during these procedures. If a patient has VWD, their healthcare team must know in advance so they can prepare and manage any potential bleeding. Doctors use medical histories to screen patients who may need testing for VWD.

VWD is harder to detect than Haemophilia since VWF performs several roles in our bodies.

Emmanuel and his team focus on improving the diagnostic structure for VWD using a panel of tests.

“We use a variety of functional tests for a more holistic approach to diagnosis VWD – a multi-pronged approach.”

VWD tests have been around for decades. One of the first tests dates back to the 1960s.

“That original test is not in itself a bad test, but it has issues with reproducibility and low level VWF detection, making it less accurate. If only that test is used, it is possible that some people with VWD will go undiagnosed or else be misdiagnosed.”

Today, we use half a dozen different tests to determine the level and activity of VWF. We refer to them as panels of tests or assays.

“Our NSW Health Pathology laboratories can investigate several different aspects of VWF. To diagnose VWD, we use several tests. Each is designed to check the different functions of VWF.”

There are six different variants of VWD.

“Our tests look at how well VWF binds to platelets and a protein (collagen) in damaged tissue, while another looks at how well VWF binds to the protein (factor VIII) that is also missing in Haemophilia A. Another test looks at the structure of VWF.

“We have a repertoire of tests available to us. Most of our research aims to improve how we diagnose bleeding diseases such as VWD so that clinicians can diagnose patients, and then manage them correctly. We can also determine which variant of VWD a person has.”

Currently, there is no genetic cure for VWD, but clinicians help patients manage their symptoms with various therapies.

Emmanuel has done a lot of research on diagnostic approaches for VWD.

“I published my first research on VWD back in 1991. Since then, I’ve published over 100 papers on the topic.”

His work has international implications too.

“When you look at VWD diagnosis around the world, it’s not diagnosed very well, particularly in developing countries where VWD is significantly underestimated.”

According to the World Federation for Haemophilia, Australia identifies 100% of patients suspected of having VWD. The USA identifies 50–70% of their estimated patients with VWD, and identification rates are less than 10% in developing countries.

Our role in pathology is to make sure that we can facilitate the diagnosis of everyone with VWD so that clinicians can best manage their risk of bleeding.

And researchers like Emmanuel are vital in this role.