Media Contact

Dotted around a handful of backyards and on farms in regional New South Wales are special flocks of chickens that play a key role in helping NSW Health Pathology protect the community from serious diseases.

They are known as ‘sentinel chickens’ and since the 1970s they have been used to give us an early warning about the presence of potentially deadly viruses such as Murray Valley encephalitis virus, Kunjin virus and Japanese encephalitis virus, which are spread via mosquitoes.

So how does the surveillance program work?

During the wet and warmer months of the year blood samples are taken from the chickens once a week and sent to NSW Health Pathology’s Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research (ICPMR) labs at Westmead for testing.

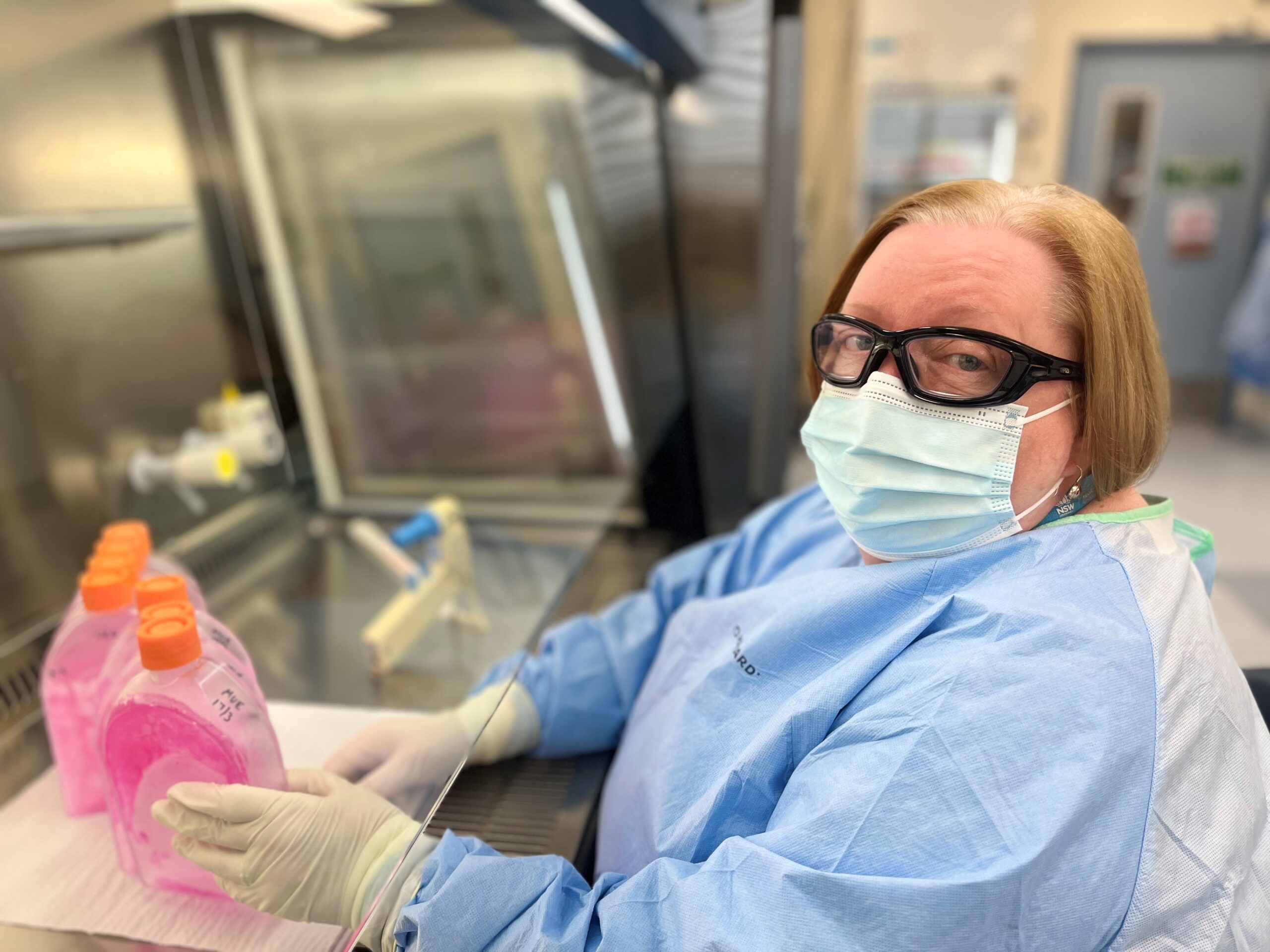

The head of the Arbovirus Emerging Diseases Unit, Principal Scientist Associate Professor Linda Hueston, explains why chickens are used and what her team is looking for when the blood samples arrive.

“Most of the viruses of interest – Murray Valley encephalitis virus, Kunjin virus, and now Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) – are circulating in wild bird populations,” she said.

“But chickens are much easier to catch and to test than wild birds.”

“In the 1990’s I developed a series of highly specific defined epitope blocking ELISA tests for Murray Valley encephalitis virus, Kunjin virus and for JEV. These tests are not just highly specific they can be used to detect antibody in any species. This allows us to compare results between animals.”

Health authorities are also testing mosquito populations for the same viruses, but A/Prof Hueston insists the information from testing the chickens is vital.

“Mosquitoes are trapped one night a week and tested, but that doesn’t give you an idea of how much virus is there, or if there is enough virus to cause transmission, which is where the chickens come in” she said.

“We estimate chickens are bitten by mozzies up to 1,000 times a night, and every time a mosquito bites it injects saliva, and the virus is in that saliva.”

“So, it’s a numbers game. With 15 chickens in each flock, the chances of finding the virus increase. As the number of positive birds in the flock increase so does the risk of virus spillover to humans.”

A/Prof Hueston said experience shows that a positive test in a chicken gives health authorities about two weeks’ notice before the virus spreads to the human population, enough time to implement public health measures in the area.

The viruses don’t harm the birds and all sentinel chicken flocks are subject to animal ethics committee approvals, as well as regular checks by veterinarians to ensure they’re properly housed and well cared for.

“They have to be in peak condition to be the best sentinels for the program, so it’s in everyone’s best interest to make sure the birds are healthy and happy,” A/Prof Hueston said.

Want to see more? One of our flocks in Griffith in the Riverina was visited in January 2023 by British YouTuber Tom Scott who made this awesome video.